Liberty and faith

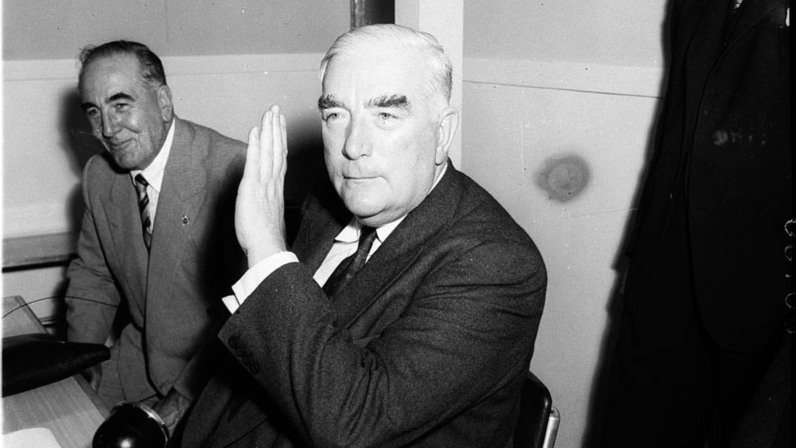

Robert Menzies’ guiding principles on the freedom to worship have assumed a new urgency in an era of rising religious intolerance. By David Furse-Roberts.

At the height of the Cold War, Robert Menzies addressed a “Freedom Rally” in Melbourne to implore his fellow citizens to stand firm for the freedoms they held dear in the face of Soviet communism. For the Australian prime minister, the most precious of these freedoms was evidently faith. In this 1960 speech, he told his audience:

That just as freedom is not easily beaten out of the heart of man, so is faith not easily beaten out of him. You cannot take thousands, millions, hundreds of millions of people who have a faith of their own, and destroy it, merely by order or command.

Referring to the fate that had befallen millions in the Soviet Union, Menzies regarded religion — and, indeed, the freedom to believe or not believe — as intrinsic to the nature of human beings. This accorded with his own understanding that “man is a spiritual animal”, a notion derived, of course, from centuries of Christian thought.

Viewing religious belief as primordial and something that long predated the state, it behoved free nations such as Australia to allow its citizens to exercise this most basic of human instincts. While Menzies took it as “a given” that the default spiritual disposition of most Australians was Christian of one kind or another, he recognised the diversity of the nation’s faith communities and therefore affirmed the primacy of religious freedom for all. Deploring sectarianism and religious bigotry, Menzies affirmed the place of not only Protestants and Catholics, but also religious minorities such as Jews and Muslims. In a 1964 speech to honour Cardinal Norman Gilroy, he remarked that “whether we be Catholic or Protestant or Jewish or Muslim, the end remains clear: We have an overwhelming duty to serve our country on the highest level and to the best of our talents.”

Affirming religious freedom for all

Menzies’ dedication to religious freedom for all was most forcefully articulated in a speech on “Freedom of Worship” delivered on 3 July 1942. Menzies took this theme directly from the “four freedoms” enunciated by the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, in his State of the Union Address to Congress on 6 January 1941. Like the American President, Menzies believed that the spectre of the Second World War provided an opportune moment to reassert the fundamentals of human liberty, which he did with a broadcast on each of the four freedoms enunciated by President Roosevelt.

When he came specifically to the “Freedom of Worship”, however, it was not only the contemporary context of the Second World War that was relevant to Menzies but also Australia’s unhappy history of sectarian strife against which he felt the need to assert the primacy of religious freedom. For Menzies, sectarian rancour between Australia’s Protestants and Catholics was not only contrary to the gospel virtue of neighbourly love, but also anathema to the principle of religious freedom. To illustrate, Menzies opened his “Freedom of Worship” broadcast with a story from his time as Attorney-General of Victoria when an “earnest partisan” upbraided him for not using his powers to ban a Catholic Eucharistic procession through the streets of Melbourne. When Menzies questioned why this person wanted the procession banned, he remonstrated that his ancestors had “fought for religious freedom” and that the procession was “an affront to every Protestant”. While Menzies similarly appreciated the religious freedom ideals of his Scottish Presbyterian ancestors, he did not see this as any justification to deny anyone else their religious freedom in the present age, be they Catholic, Protestant, or otherwise. He well understood that a commendable enthusiasm for one’s own faith could all too often, but by no means always, lead to suppression of another’s faith.

As such, Menzies himself identified as a Protestant but stressed that freedom of religion was “freedom for all, Catholic or Protestant, Jew or Gentile, and that to deny it was to go back to the dark ages of man.” He said that such freedom “must mean freedom for my neighbour as well as for myself.” This was a principle he had long practised, telling his own father that being the young Member for East Yarra meant “being the Member for the lot” — for “Presbyterians, Anglicans, Roman Catholics, [and] Brahmins for all I know.”

For Menzies, the freedom of belief also meant the freedom of unbelief. It encompassed not only people of all faiths but also those of no faith, such as rationalists, naturalistic sceptics, atheists, and agnostics. As unappealing as atheism may have been to Menzies as a belief system, he nonetheless affirmed the freedom “to worship or not to worship”. Of atheists and agnostics, he remarked: “There have been honest and indeed noble men in this world who have never been able to find a God. Are we to deny them their place?” Menzies’ commitment to religious freedom was based not simply on a sense of fair play but also on his appreciation of human diversity, not least in faith and worship. He observed that “we are a diversity of creatures, with a diversity of minds and emotions and imaginations and faiths. When we claim freedom of worship, we claim room and respect for all.” He concluded by affirming that “each of us has his own faith, and no mortal man may compel it or suppress it. That is, I believe, a freedom worth fighting for.”

Amid this spiritual diversity, Menzies also appealed for human unity, holding that: “the things which unite us as human beings are deeper and more lasting than the things that divide us as members of different creeds. They should be a source of harmony and unity, not of discord and strife; of tolerance and generosity not of intolerance and bigotry.” In affirming this, Menzies was not seeking to diminish the very real differences existing between faiths, or, indeed, the disparate strands within a particular faith such as Christianity or Judaism. He was, instead, reminding citizens that for all their spiritual differences, concord on universal human values was still possible and indeed essential. A free and civil society could be comprised of people who were either happily Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, Muslim or agnostic, yet still be committed to the virtues of charity, justice, kindness, generosity, patience, temperance, and humility. For this formula to work, Menzies held that tolerance was an essential ingredient.

By “tolerance”, however, Menzies did not imply acceptance of every belief and practice as morally neutral or equivalent, as the word is frequently interpreted to mean in today’s relativist parlance. It was, on the contrary, a recognition that every other honest person “who, hating the same evil, will see a different road by which to come against it.” Elsewhere, Menzies asserted similarly that:

Tolerance does not mean flabbiness. Tolerance of each other does not mean that we condone evil things or that we are not prepared to fight against evil things. Tolerance is mutual understanding, forbearance, a desire to assemble ourselves every time there is a common cause to be served.

Applied to religious freedom in Australia, this meant that citizens could entertain their own differing conceptions about God and other things spiritual, yet still share a degree of consensus on what was good and evil and thereby work together in the furtherance of common causes in civil society. Menzies had witnessed an example of this in Australia’s private education realm where Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish schools each shared a vision for inculcating the rising generation of citizens with moral character and faith in something greater than themselves.

Historical roots of Menzies’ belief in religious freedom

As a Presbyterian, Menzies took particular pride in what he saw as the contribution of his spiritual ancestors, the seventeenth-century “Scottish Covenanters”. In reality, however, Menzies’ attitudes to religious freedom aligned more closely with the enlightened, liberal outlook of the English Nonconformists, the class of dissenting Protestants from the Church of England whom Timothy Larsen termed the “friends of religious equality”. Borne of their own experience of persecution by the established Church of England in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Nonconformists emerged as early advocates of religious liberty, supporting both Catholic and Jewish emancipation as well as religious equality under the law. Through his mother’s Cornish Methodist lineage, Menzies had some historical links to eighteenth and nineteenth-century English Dissent, and the close ties of these Protestants to the English Whig/Liberal movements helped to explain how their religious liberty-affirming ideals made their way into the consciousness of a twentieth-century Australian Liberal like Menzies.

Best exemplified by the likes of Edmund Burke and T.B. Macaulay — both of whom Menzies was fond of quoting — English Whiggism, at least in its political party form, dated back to the First Earl of Shaftesbury (1621–1683). Lord Shaftesbury founded the Whig Party in 1679 and was patron of the English Whig philosopher, John Locke (1632–1704). It was in this Whig stream of thought from which Menzies drew his ideas on religious freedom. As supporters of religious liberty, Locke, Shaftesbury, and the early Whigs were advocates for the rights of dissenters and sceptical of all forms of clerical authority. In accordance with Nonconformist thought, Locke reasoned that religion was a spiritual matter. In the First Treatise on Government (1660), he wrote that “the great business of Christian religion lies in the heart”, not in external behaviour.

Menzies, likewise, held that religion was essentially a matter of the heart, claiming that “in the heart of every man, whatever he may call himself, is that instinct to touch the unknown, to know what comes after, to see the invisible.” Following on from Locke, Menzies stood in the Whig tradition of Burke who similarly championed religious liberty to achieve a broader toleration for Roman Catholics and Protestant Dissenters from the established church. Appealing to the primacy of conscience, Burke once stated that “if ever there was anything to which, from reason, nature, habit, and principle, I am totally averse, it is persecution for conscientious difference in opinion.”

Menzies’ conception of religious freedom was moreover indebted to the later Victorian-era liberalism of figures such as John Stuart Mill (1806–1873). Menzies’ own philosophy of Liberalism differed from that of Mill in some important respects — most notably in being non-utilitarian, grounded in tradition and informed by a theistic, Christian worldview. Nonetheless, he enthusiastically embraced the Victorian philosopher’s zeal for the basic human freedoms of thought and expression that were relevant to religious faith. Praising Mill’s seminal 1859 essay On Liberty, as still “full of freshness and truth”, Menzies applauded Mill’s assertion that an individual not only had the freedom to hold an opinion but also the freedom to have that opinion challenged. Menzies thus quoted Mill:

Complete liberty of contradicting and disproving our opinion is the very condition which justifies us in assuming its truth for purposes of action, and no other terms can a being with human faculties have any rational assurance of being right.

Given the competing claims of different faiths in society, this meant that one’s personal belief was poorly founded and weakly held if it was not able to resist the onset of another person’s critical mind. Elsewhere in Mill’s essay, Menzies would have agreed with the philosopher’s assertion that an individual’s liberty of conscience and religious belief was essentially unbounded:

This, then, is the appropriate region of human liberty. It comprises, first, the inward domain of consciousness; demanding liberty of conscience, in the most comprehensive sense; liberty of thought and feeling; absolute freedom of opinion and sentiment on all subjects, practical or speculative, scientific, moral or theological.

His outlook on the freedom of worship may have had its roots in the Whig liberalism of John Locke, but it was the nineteenth-century classical liberal thought of John Stuart Mill that contributed to its full flowering.

Religious freedom and the Liberal Party

When Menzies founded the Liberal Party of Australia in 1944 from the remnants of the old United Australia Party, he held that it was important for freedom of religion to be affirmed explicitly in the blueprint of the new party. The third objective of the October 1944 platform provided that, “We will strive to have a country in which an intelligent, free and liberal Australian democracy shall be maintained by freedom of speech, religion and association.”

The subsequent November 1954 platform went a little further, containing two objectives pertaining to religious freedom. The thirteenth affirmed: “We believe in the great human freedoms: to worship; to think; to speak; to choose; to be ambitious; to be independent; to be industrious; to acquire skill; to seek and earn reward.” This was followed by the fifteenth which stated: “We believe in religious and racial tolerance among our citizens.” The objectives of both platforms embodied the principles that Menzies had articulated in his “Freedom of Worship” broadcast. For the manifesto of a party committed to championing the fundamentals of liberal democracy, freedom of worship and religion represented a non-negotiable article of faith.

Campaigning for the Liberal Party at the 1949 election, Menzies again affirmed his party’s dedication to religious freedom. Reiterating the basic principles of liberal democracy, Menzies declared:

The real freedoms are to worship, to think, to speak, to choose, to be ambitious, to be independent, to be industrious, to acquire skill, to seek reward. These are the real freedoms, for these are of the essence of the nature of man.

Some years into his post-war prime ministership, Menzies remarked at a 1961 naturalisation ceremony on how new immigrants to Australia were able join a country where such freedom abounded:

to come to a country where freedom will be defended by everybody, whatever political party he may belong to, whatever religion he may profess, where everybody is agreed that we are free people, free … to pray as we want to pray, to speak as we want to speak, to assemble as we want to assemble.

Addressing his audience of new citizens, a large proportion of whom had fled European countries oppressed by either fascist or communist dictatorships, he celebrated Australia as a beacon of freedom for all, whatever the religious beliefs or otherwise of its people.

To be sure, Menzies’ pronouncements on religious freedom had a definite historical context in President Roosevelt’s declaration of the “four freedoms” in 1941, followed by the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. The UN Declaration had made the following provision for religious freedom in Article 18:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

The Declaration essentially embodied the principles that Menzies had consistently articulated throughout his public life. Together with the UN and the leaders of the free world, Menzies was dedicated to championing religious liberty in an era when such liberties had been under grievous assault from Nazism and fascism, together with communism. It was the ideal of Western leaders such as Roosevelt and Menzies that religious freedom for all would form one of the great pillars of the new liberal international order.

Menzies’ relevance for us today

In Australia and elsewhere, religious freedom remains a pressing issue and the importance Menzies accorded to this basic principle is highly applicable to the present day.

In contemporary Australia which is home to a multiplicity of Christian traditions and religious faiths that, for the most part, amicably coexist, the freedom of religion in teaching, practice, worship, and observance is highly prized. With the sectarian rancour and discrimination of earlier generations banished to the past, religious freedom is in some respects less inhibited now than in Menzies’ time. On the other hand, the advance of secularism has brought new challenges to the free exercise of religious beliefs and practices that had hitherto gone largely unchallenged. This has been particularly pronounced in the realm of sexual ethics where traditional attitudes to marriage, typically informed by religious sensibilities, have been on a collision course with the modern, mostly secular outlook affirming of same-sex marriage. With the right for such attitudes to be expressed in the public square becoming increasingly contested, questions of religious freedom have been brought into sharper focus.

With the tension between religious freedom and non-discrimination on sexuality grounds surfacing only relatively recently, this was not a predicament Menzies faced in his own time. The religious freedom principles he enunciated, however, suggest that he would most likely have lent firm support to legislative measures to protect religious freedom from undue impingement by competing interests.

His ardent support for church schools to practice their faith and his express resolve to protect the rights of citizens to think, worship, pray, and assemble according to their own conscience stand decidedly at odds with modern threats to some of these liberties. These include the censorship of more contentious religious views on social media, the “de-platforming” of religious groups from venues and public spaces, instances of employees being fired for their religious beliefs, and calls to strip religious schools of their rights to engage staff in accordance with their faith and values. By contrast, Menzies would affirm the necessity for civil society to afford institutions and individuals of faith the freedom to be simply themselves.

To this end, Menzies would endorse many of the proposals of the Australian government’s 2018 Religious Freedom Review to accord religious liberty greater protection. As he had said in his broadcast on “Constitutional Guarantees” in November 1942, he would be “among the first to act promptly to destroy the threat” to religious freedom in Australia. Thus, for all the radical changes in the religious beliefs and moral mores of society since Menzies exited public life in the 1960s, his guiding principles maintain a timeless quality and urgency.

Religious freedom as love for neighbour

In contrast to many contemporary proponents of religious pluralism, Menzies’ unwavering commitment to religious freedom was not simply borne of a postmodernist worldview affirming of moral and religious relativism. On the contrary, it was a disposition that had deep historical roots in both the Christian tradition and liberal thought. As a Christian believer himself, Menzies regarded religious freedom as an expression of the neighbourly love his own faith preached, but not necessarily always practised. In Menzies’ own words, religious freedom “must mean freedom for my neighbour as well as myself.”

For Menzies, religious freedom, in its truest sense, was not simply about an individual claiming the right to practise his or her own personal faith, but about affording that same freedom to one’s fellow citizen, whatever their faith or creed. The ideal of religious liberty stemmed from the classical Christian notion that faith was a matter of personal choice and individual conscience that could never be oppressed or compelled from the outside. As Robert Wilken wrote in Liberty in the Things of God, “Liberty of conscience was born, not of indifference, not of scepticism, not of mere open-mindedness but of faith.” Complementing this Christian stream of thought was the philosophy of liberalism, developed over centuries by figures from John Locke to John Stuart Mill, that affirmed the primacy of religious toleration in a free society.

To Robert Menzies, freedom of worship and religion was a pillar of his own Liberal philosophy, as well as a fruit of his religious faith.

This article was first published on ABC Religion and Ethics. David Furse-Roberts is the author of God & Menzies: The Faith that Shaped a Prime Minister and his Nation, Jeparit Press, 2021. Click here to buy the book.