Taking the lead

Source: Instagram

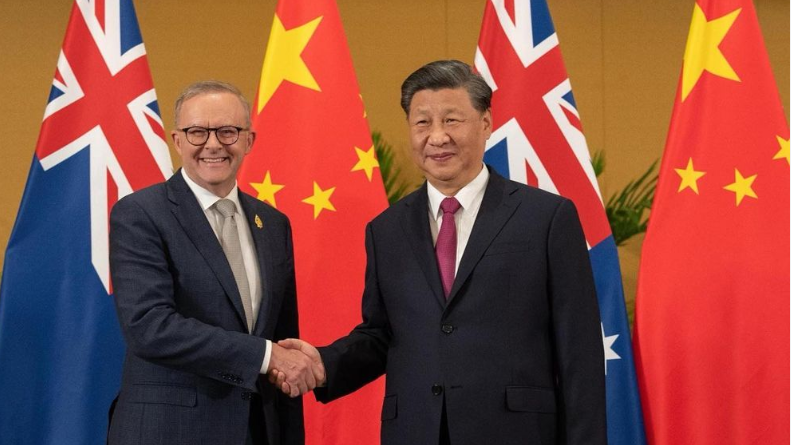

The bilateral visit to China will be a test of anthony Albanese’s personal capacity to persuade President Xi Jinping on the strategic issues facing Australia and the world. By georgina downer.

Taking pot shots at prime ministers has long been a national sport in Australia.

What they wear, how they speak, too many interviews or too few interviews, carrying a hose or not carrying a hose.

What’s a poor PM to do?

One thing that triggers particular controversy is the frequency of prime ministerial travel.

Travel bills are added up, we count the kilometres flown (just how many times to the moon and back?) and now we assess the tonnes of carbon emitted.

Australia’s longest-serving prime minister Robert Menzies visited over 20 countries throughout his 18 years in office, travelling every full year he was in office except 1940.

Trips took much longer then, and he was the first prime minister to travel by plane in 1941.

Kevin “747” Rudd made 12 overseas trips in his first year in office, but Scott Morrison went on 29 international trips in just over three-and-a-half years as PM, two of which were severely hampered by COVID related travel bans.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has travelled prolifically since he took office in May 2022 and this weekend he will embark on his 18th overseas visit in 18 months.

All this travel begs the question, is it worth it?

There are of course the regular international meetings such as APEC, the G20, the East Asia Summit, the UN General Assembly, the Pacific Islands Forum and more recently the Quad Leaders Summits.

Australia is a middle power and these need to turn up otherwise they may find they are no longer a middle power.

Does Australia want or need to be a middle power?

Those with the title can exert an influence on the international system to suit their interests much more so than small powers who must accept things as they are.

Or as Thucydides put it, “the strong do as they can and the weak suffer what they must”.

Over 18 years in office, Robert Menzies’s influence grew so much that he was considered a significant international statesman well beyond the influence Australia itself could expect to command.

He was the elder statesman of the Commonwealth when it mattered much more than it does now and played a leading role in the Suez Crisis on behalf of Britain and France.

The time away from Australia can be hazardous for prime ministers and leave them open to accusations of not focusing enough on the domestic concerns of their constituents.

Absence can also create opportunities for internal political opponents, as Robert Menzies experienced in 1941 when he was out of Australia for four months visiting Britain, Singapore, Cairo, North Africa, Portugal and the US.

His wife, Dame Pattie, cautioned him before the trip that he would be out of office within six weeks of his return and she was proved correct as he lost support within the Coalition and had to resign.

These risks aside, there is huge value in bilateral visits for Australian prime ministers.

Bilateral visits are important to build relationships with the leaders of allies and partners which is why new prime ministers always make early visits to the US, China, Japan and the Pacific.

Leader to leader diplomacy can deliver big time.

Just think of the bromances of John Howard with US President George W Bush which resulted in the Australia-US FTA, Tony Abbott and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe which delivered the Japan-Australia Economic Partnership Agreement and Malcolm Turnbull and Indonesian President Joko Widodo which reset Australia-Indonesia relations after the execution of two of the Bali Nine.

But leaders are human beings too. They don’t always get on.

Robert Menzies famously didn’t warm to Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, nor did Billy Hughes manage to charm US President Woodrow Wilson, who called Hughes a “pestiferous varmint”.

There is no argument Albanese’s visit to China is in Australia’s interests, despite it taking him away from Australia yet again.

Over the last few years Australia did the world a favour, standing up to China’s aggression and wolf warrior diplomacy.

The nation is a strong case for the importance of middle powers and their ability to exert influence on the international order.

Without giving so much as an inch, Australia has seen China back down, release Australian journalist Cheng Lei, abandon unreasonable tariffs on Australian barley with plans to do the same on Australian wine.

The bilateral visit to China is an opportunity for Albanese to reset relations at a leader level, but also remind China that where our interests converge, we will work together, but where they diverge, Australia has and will continue to stand up for itself.

The outcomes of the visit have already been written and well publicised in the media.

What is really important is for Albanese to demonstrate he has the intellect and the personality to persuade President Xi Jinping on the strategic issues facing Australia and the world.

That is where the capacity of the individual leader matters much more than the media spin or DFAT talking points.

Georgina Downer is CEO of the Robert Menzies Institute and a former diplomat.