The Choice of Reason

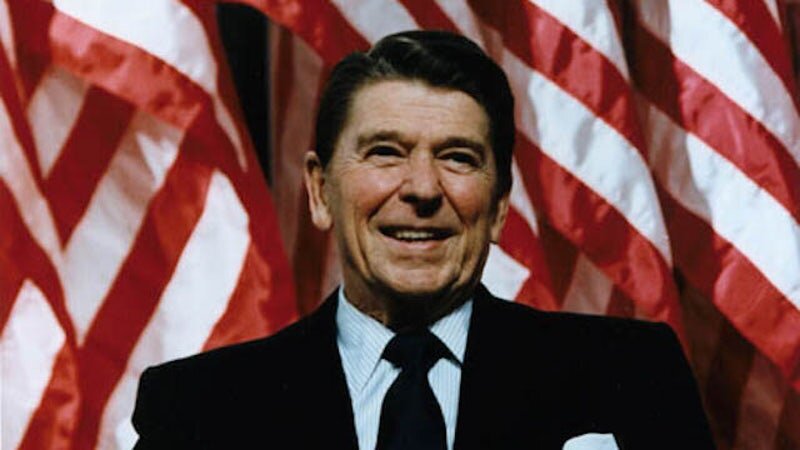

Freedom and individualism are timeless principles, as Ronald Reagan’s first major speech, delivered 55 years ago this month, reminds us. By Sean Jacobs.

“I have an uncomfortable feeling that this prosperity isn’t something on which we can base our hopes for the future,” Ronald Reagan said in A Time for Choosing, one of his most famous speeches, 55 years ago last month.

Reagan was right to warn about the United States’ creeping complacency in an increasingly hostile world, especially from the nuclear-armed Soviet Union, but the prosperity to which he referred was positively tenacious compared to today’s. Reagan could at least rely on social cohesion and productivity. These days, the developed world is beset by debt, social fragmentation and ennui, which are vividly displayed almost daily in environmental protests around the world.

The speech was delivered as support for 1964 Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater but, in effect, it launched Reagan’s own political career, which culminated in his historic presidency from 1981 to 1989.

Reagan admits that he had been associated with the Democrats all his life, but now he sees fit to “follow another course”. His current successor, Donald Trump, made a similar transition, coming from outside the political machine and also being mostly previously associated with Democrats. Whether Trump becomes another Reagan remains to be seen.

Today Reagan is often remembered for being a relaxed and even cavalier President. This speech, outlining the solid foundation of his beliefs, proves otherwise. In it he cites Plutarch, the Founding Fathers and patriots of Concord Bridge (the 1775 "shot heard round the world") while also referring to agricultural and housing policy, juvenile delinquency, weekly incomes, decolonisation and foreign aid. Citing Department of Labor statistics and an incapacity of the federal government to balance a budget, to the impractical real-world effects of Senate Bills and Supreme Court rulings, Reagan cuts a master class for a budding public figure – the marriage of high principle to practical politics.

His starting point is, as the title of his speech implies, a choice. “Either we accept the responsibility for our own destiny, or we abandon the American Revolution and confess that an intellectual belief in a far-distant capital can plan our lives for us better than we can plan them ourselves.”

Although covering significant policy and philosophical terrain, there is one theme that ties these issues together – common sense – which he repeatedly applies to government incompetence. It is not a difficult target to hit. He asks why, for example, the US Defense Department runs 269 supermarkets that “do a gross business of $730 million a year, and lose $150 million.”

On agriculture, he notes that, over the previous decade, “we have seen a decline of five million in the farm population, but an increase in the number of Department of Agriculture employees.”

Or this: the federal government spends “$4,700 a year for each young person we want to help” when “we can send them to Harvard for $2,700 a year.” Not that he was proposing it, though. “Don’t me wrong – I’m not suggesting Harvard has the answer to juvenile delinquency.”

Regarding “the conspiracy of silence about the people enslaved by the Soviet Union in the satellite nations” he notes the ‘two steps forward one step back’ nature of American foreign assistance, foretelling the excesses of foreign aid. “We set out to help nineteen war-ravaged countries at the end of World War II,” he says. “We are now helping 107.”

And turning to subsidised housing, he tells the story of an East American businessman who “sold his property to Urban Renewal for several million dollars” but then “submitted his own plan for the rebuilding of this area and the government sold him back his own property for 22 per cent of what they paid.”

Little has changed since then. Not only does government waste and incompetence continue to plague Western politics but it is now joined by an avoidance of hard choices. Douglas Murray recently wrote in The Spectator “that on issue after issue we have to arrive at decisions that offend nobody and harm no one.” Reagan, too, observed, “any time we question the schemes of the do-gooders, we are denounced as being opposed to their humanitarian goal.”

As President, Reagan was known for a folksy charm and good humour. “Honey, I forgot to duck,” he told wife Nancy after being shot in March 1981. “I just hope you’re all Republicans,” he also joked to physicians just before entering emergency surgery.

The current political leaders of the US, Australia and Britain all emulate Reagan in some way. For Donald Trump and Scott Morrison, emulating Reagan helped them win office. Boris Johnson's carefully cultivated blend of flippancy and seriousness may yet achieve likewise when he too faces the people next month.

A former actor, Reagan did not need the stress of public life, especially as a conservative, which put him on the wrong side of fashionable arguments, resulting in lost allies in influential quarters. But his toughness and intellectual conviction compelled him.

Progressives will always use inequality for political advantage, but Reagan had a homespun answer to this too. “Today there is an increasing number who can’t see a fat man standing beside a thin one without automatically coming to the conclusion the fat man got that way by taking advantage of the thin one,” he said.

Reagan resisted the feel-good urge to redistribute wealth even at a time of relative prosperity. It is an urge that must be resisted even more strenuously now. People don’t become rich from handouts, and nations don’t become strong from welfare.

Sean Jacobs is the author of Winners Don’t Cheat: Advice for young Australians from a young Australian (Connor Court 2018) and writes at www.seanjacobs.com.au.