The wealth of the nation

The Menzies years were a period of sustained prosperity characterised by policies that stimulated economic growth and permitted it to persist. By Henry Ergas and J.J. Pincus.

In the 1950s and well into the 1960s, Australia, together with much of the Western world, experienced a long economic boom – of steadily advancing living standards, remarkably low unemployment and fulfilled expectations of low inflation – which erased many of the ill effects the traumas of the 1930s Depression and the Second World War had inflicted on the cohorts that experienced them. Thanks to that boom, the Australia of 1966 was vastly more prosperous than that of 1950; it was also more equal in terms of the distribution of income and wealth.

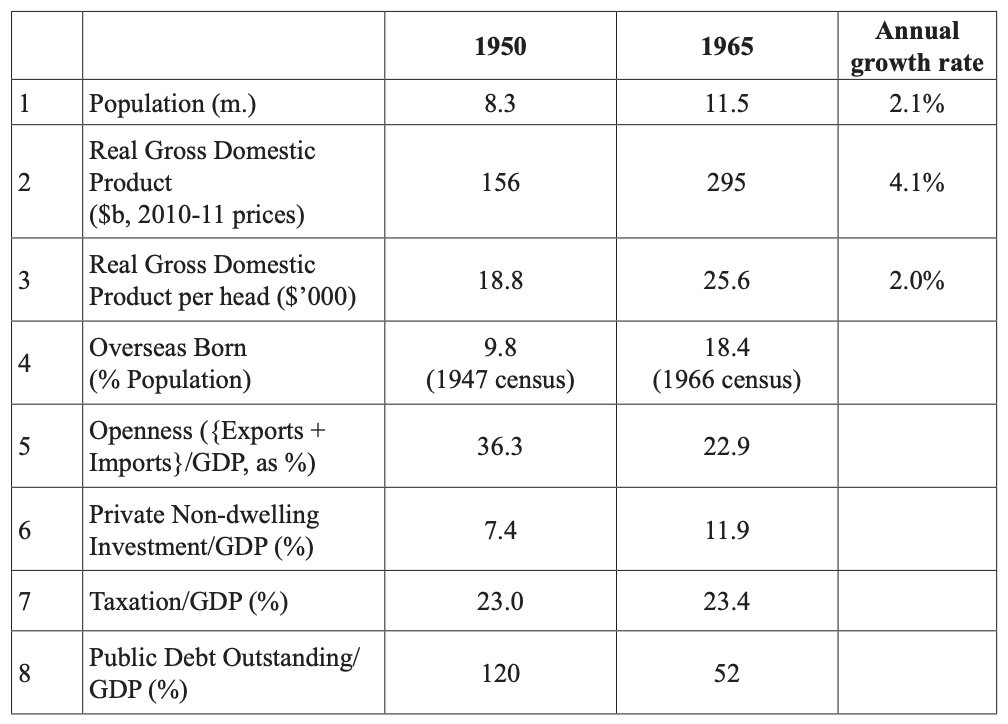

Table 1 Population and Economy, 1950 and 1965: selected data

Sources: Rows 1-6: M. Butlin, R. Dixon and P. J. Lloyd, “Statistical Appendix: selected data series, 1800-2010”, in S. Ville and G. Withers, eds, The Cambridge Economic History of Australia, Cambridge University Press, Port Melbourne, 2015. Rows 7, 8: W. Vamplew (ed), Australians. Historical Statistics, Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates, Broadway, NSW, 1987, GF6, 256.

And it was far larger also, in economic and social terms. During the Menzies era, the Australian population grew by almost 40 percent, faster than in the world as a whole (34 percent) or the United States (30 percent). This was the height of the post-war “baby boom”: the fertility rate peaked in 1961 at 3.55 – Menzies had introduced child endowment for multiparous families in 1941, in an effort to postpone an increase in the Basic Wage; it was extended to all children in 1950. But even with the “baby boom”, net immigration contributed almost four-tenths of the population increase over the whole period, and over half in the late 1940s and early 1950s – a far higher proportion than in Canada or the United States – as the Menzies Government adapted and extended Labor’s immigration program. Reflecting the impact of migration, there was a doubling in the proportion of Australians born abroad (to more than 18 percent) between the census of 1947 and that of 1966. As the migration program proceeded, the sources of the foreign born population changed too, with “New Australians” increasingly coming from Southern Europe.

At the same time, national production, measured as GDP adjusted for inflation, almost doubled in size: this implies a growth rate twice as fast as that of population, and that had not been experienced for an extended period since the boom that followed the gold rushes.

Table 2: Rates of output increase in Australia (percentage rates of increase per annum in real G.D.P.)

Source: W.A. Sinclair (1976). The Process of Economic Development in Australia. Melbourne: Cheshire, 212.

Given the rapid growth of population and production, it is remarkable that GDP per head, an admittedly imperfect index of living standards, grew at two percent a year: as fast as during the period from 1991 to 2010, which is widely considered to have been a period of great prosperity.

With the economy growing strongly, unemployment was extraordinarily low in absolute terms – in one month in 1951 (admittedly at the height of the wool boom), the number of registered unemployed in South Australia was down to only three people – as well as compared to other high income countries. Despite a slight fall in the participation rate, the supply of labour was increasing rapidly, but demand for labour was also growing fast, boosted by the private and public infrastructure demand of immigrants and especially by private non-dwelling capital formation, which rose from 7.4 percent of GDP in 1950 to almost 12 percent of GDP in 1965.

Figure 1: Unemployment Rate

Source: Henry (2007) from ABS Catalogue Number 6204.0.55.001, 6202.0 and Reserve Bank of Australia

Figure 2: Prices and wages (year average)

Source: Henry (2007) from ABS Catalogue Number 5204.0, 6302.0 and Reserve Bank of Australia.

Yet, once Arthur Fadden’s “horror budget” of September 1951 had brought the inflation unleashed by the 1949-50 surge in wool prices under control, low unemployment was accompanied by low inflation, especially in the 1960s (when Australia’s inflation rate was well below that of the other advanced economies). In 1953, the Arbitration Commission abandoned automatic quarterly indexation of the basic wage, as being inconsistent with application of the “capacity to pay” principle to an open economy, such as Australia’s. In the event, although the metal trades industries became the wage setting leader, and despite the rise in claims for “margins for skill” (and later in the period, in over-award payments, which provided some flexibility in wage setting), there was no serious “wages breakout” until the Whitlam Government came to office. On the contrary, as Blanche d’Alpuget reported, “when the Minister for Labour, Billy MacMahon, travelled abroad, he was lionized by foreign counterparts who wanted to know how Australia managed things so well”.

Far-reaching changes in the structure of the economy accompanied rapid growth. Over the period to 1965, agriculture declined markedly, shrinking from 24 to nine percent of GDP (Figure 3); but rural industries still dominated Australian commodity exports, with wool alone accounting for almost 30 percent of exports by value at the end of the period. The terms of international trade were moving against primary exporters like Australia; moreover, within Australia, the prices of the inputs farmers purchased increased more rapidly than the prices at which they sold their outputs. However, with mechanisation, innovation in varieties and techniques, and application of science, especially of pest control – myxomatosis (although invented much earlier) was introduced in 1950 – productivity in the farm sector was still growing faster than in the non-farm market sector at the end of the era.

Rapid productivity growth affected relative incomes. Despite a decline in the “product” terms of trade (that is, the ratio of prices farmers received to prices farmers paid), rapid productivity growth in agriculture meant that the “factor” terms of trade – the factors of production Australian farmers had to devote to paying for the factors of production embodied in the goods and services they purchased – did not deteriorate by anywhere nearly as much, and especially when the growth in agricultural productivity was at its peak, may actually have been improving. That encouraged agricultural output to expand, which it continued to do even as prices fell. So notable was the resulting growth that a Treasury retrospective, published in 1966, confidently concluded that:

… Despite the fears voiced from time to time about the future of Australia’s exports of primary products, results so far seem to show that increases in production can more than offset the effect on export proceeds of falling prices. Whereas the future of export prices is problematical, experience in Australia and elsewhere suggests that the upward trend in productivity in the main primary industries can continue.

Figure 3: Industry Shares

Source: Ville and Withers (2015), Table A1, 559

Figure 4: Terms of Trade and Inflation Rate

Source: Henry (2007) from ABS Catalogue Number 5204.0 and Reserve Bank of Australia.

Even so, the most rapidly growing productive sector was “Other” – services and construction, which rose from 48 to 63 percent of GDP. It was also notable that manufacturing reached its century peak share of 29 percent of GDP in 1958; and that, despite the stirring of a minerals boom at the end of the period, mining barely grew from two percent of GDP.

Overall, this was a rare period – only repeated in the 1990s – when strong growth in Australia did not coincide with a sustained increase in world demand for its natural resources, and hence when growth was not led by the resource industries.

Rather, the growth process was largely inward-looking. Although the economy was made more open to the inflow of capital and labour from abroad, high levels of import protection meant that international trade fell in importance. This can be seen from the sharp decline in the degree of (trade) openness, measured by the ratio of exports plus imports to GDP that is shown as line 5 of Table 1 and in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Trade intensity (nominal exports plus imports as a share of GDP)

Source: Henry (2007) from ABS Catalogue Number 5204.0 and Reserve Bank of Australia.

Elsewhere, in the USA, the UK and most advanced economies, openness rose or held steady. World trade grew faster than world production, in part due to the efforts of the United States to encourage countries to reduce their import barriers, especially in the various “rounds” of negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. Australia held back, pleading that it was an intermediate economy: rich but still developing, and reliant on primary rather than manufacturing exports. The refusal of most advanced economies to bind (that is, commit to not increase) the tariff and non-tariff barriers they imposed on agricultural trade, much less reduce them, entrenched Australia’s reluctance to scale back its own protectionist measures. Moreover, Australia preferred bilateral to multi-lateral trade agreements, or took unilateral action.

But it would be dangerous to view openness too narrowly. Although the economy’s trade intensity fell, inflows of factors of production – capital, labour and technology – increased materially, greatly influencing the course of economic development (discussed further below). Additionally, despite the decline in openness to international trade, the economy remained highly vulnerable to external constraints; these manifested themselves in balance of payments crises in 1951-52, 1954-55 and 1955-56, and then 1960-61. Each of those crises, in which the country’s holdings of foreign exchange dropped suddenly, was associated with internal booms that caused a surge in imports. Given the constraint of a fixed exchange rate, governments responded by using monetary and fiscal policy to dampen economic activity; the 1951-52 crisis also led the Government to impose quantitative import restrictions in March 1952 (which remained in place until 1960) as a way of stemming the loss of foreign exchange. Tightening fiscal and monetary policy inflicted a cost in terms of economic growth: GDP shrank by about one percent in response to the 1951 “horror budget” and by two percent in 1960-61, while growth came to a standstill in the downturn that followed the balance of payments crisis of the mid-1950s.

The result was to highlight the tension between the Government’s central goals of rapid growth and full employment, on the one hand, and the maintenance of external balance – fundamentally, the ability to defend the exchange rate – on the other. How that tension could be resolved was at the heart of economic policy.

This is an edited extract of a chapter by Henry Ergas and J.J. Pincus from Menzies: The Shaping of Modern Australia, edited by J.R. Nethercote (2016, Connor Court). Click here to buy the book