Understanding Menzies’ words

the principles that underpin menzies’ famed phrase ‘homes material’, ‘homes human’ and ‘homes spiritual’ are more relevant than ever, providing instructive lessons for the liberal party. by stuart Coppock.

Introduction

John Howard sagely and with perspicacity warned against the Liberal Party of Australia descending into a ‘woe is us’ mentality following the loss of Government in NSW in March 2023. This same advice also applies to the party’s defeat in the Aston by-election of the same year, the first ever by a Federal Opposition.

Historically loss of government means the first term in Opposition is potentially numbing, the second term can be confronting but restorative of political competency. But times are changing. A one term government is now more of a reality. Particularly where incumbent governments are dominated by events or create circumstances through questionable administration. What has not changed in any political turnaround is the needed work of solid policy review. Indeed, former prime minister Tony Abbott has been calling for this. Such work takes effort and ideally starts with what a political party sees as its belief and principles. This work is the backbone for future electoral success and points to long-term and effective government. With such work, relevancy can be found more so in history books rather than in pollster’s reports.

The words ‘person’ and ‘individual’

Language and context and actions are determinants of understanding many things. Through these lenses, further insights into Menzies’ ‘Forgotten People’ speech and what followed might be welcome thought to receptive minds.

In 1942 one of the remarkable things in Sir Robert’s radio broadcast is the use of the word ‘people’ instead of the word ‘individual’ to describe the human creature generally. To make sense of how Menzies used the word ‘people’ is relevant. The word ‘people’ is the plural of the word ’person’. Person has its etymology in the Greek word ‘prosopon’ meaning ‘mark, face’, or ‘personage’. The face was a mark used in Greek theatre but in the 4th century became associated with substance and eventually gave us our word ‘essence’.

The Oxford Dictionary of Etymology tells us the word ‘person’ is the living body of a human being. The Greek word carries within in it the notion of a relationship; ‘towards a face’. Some have taken this relationship one step further to imply ‘kinship’. The Greek term today in our society means the external, undivided representation or manifestation of an individual. The word we know as ‘individual’ is derived in Greek from the same word that we obtain the word ‘atom’. Traditionally, atom was the smallest part of an element. It was a word used in the way we put the prefix ‘im’ before a word to get the opposite meaning, such as ‘possible’ and ‘impossible’. In this context the Greek word individual is an opposite to a person. The word individual is defined today as meaning single and separate. Menzies’ language points to an understanding that, 80 years on, might be misunderstood with the emphasis nowadays on the ‘individual’!

The relevance of this today is the notion of a relationship contained within the meaning of a ‘person’ which makes that person a part of a community or a society. An individual points to the individual as a singular concept without a community. The person carries the individual. The individual is within the person. Each person is unique, and each person has individual characteristics or habits because of that uniqueness. This uniqueness and the choices associated with this and being part of a society are at the heart of the ‘Forgotten People’ radio broadcast. Australians sing in the fourth stanza of the song ‘I am Australian’ the words: ‘We are one, we are many’. This is a statement of personhood, community, and individualism.

Forgotten People radio broadcast and its context

The opening paragraph of the ‘Forgotten People’ broadcast states that the Australian community is one and not different (and conflicting) parts. The segment of the broadcast where the phrase ‘the forgotten people’ is found touches upon themes of equality of people and equality of opportunity. The role of looking after others in, and as part of, our society is implied in these themes.

CS Lewis in November 1941 in Great Britain at Oxford, six months earlier than the Menzies broadcast, gave what many consider to be his greatest sermon, which is known by the name ‘The Weight of Glory’. It was not published until after WWII.

The opening paragraphs of the sermon note that of a poll (if taken in 1941) of 20 young persons, 19 would use the word ‘unselfishness’. Lewis noted in a different past time the same poll would have people saying the word ‘love’. Lewis said that this was a move to the negative from the positive. This was so because one answer is a concern about oneself and the other a concern for others.

In the same sermon Lewis speaks of the ‘differentiated society’ through an individual’s vocation. I summarise, but the point here is that society is comprised of many parts to make the whole. What is within both Menzies’ radio broadcast, Lewis’ sermon and in Liberal Party material in the early 1950s, which will be referred to later, is clear recognition of the freewill or choice that resides in the person and therefore the individual.

In May 1932, eight years before the Forgotten People broadcast, Lord Atkin in the celebrated ‘snail in the bottle’ or ‘paisley snail’ case established the ‘neighbour principle’ in our common law. It was a secularisation in legal principle of a principle found in four biblical references. Note that CS Lewis used the word ‘love’. The relevance to Menzies’ radio broadcast is, he took the neighbour principle and applied it to a political philosophy of Australian Liberalism. A person is in a society and where that society is a community, each person looks out for each other through a concern for others. Within this circumstance there is still an individual’s capacity to exercise a choice for betterment through owing a home, not a house, and education expressed in the phrase: ‘homes material’, ‘homes human’, and ‘homes spiritual’.

Menzies wrote:

‘What do I mean by "homes material"? The material home represents the concrete expression of the habits of frugality and saving "for a home of our own”.

‘If human homes are to fulfill their destiny, then we must have frugality and saving for education and progress. Human nature is at its greatest when it combines dependence upon God with independence of man … the greatest element in a strong people is a fierce independence of spirit … This is the only real freedom, and it has as its corollary a brave acceptance of unclouded individual responsibility. The moment a man seeks moral and intellectual refuge in the emotions of a crowd, he ceases to be a human being and becomes a cipher. The home spiritual so understood is not produced by lassitude or by dependence; it is produced by self-sacrifice, by frugality and saving.’

Belonging to a community is very distinguishable from the description of ‘intellectual refuge in the emotions of a crowd’ - or ‘wokeism’ in today’s terms.

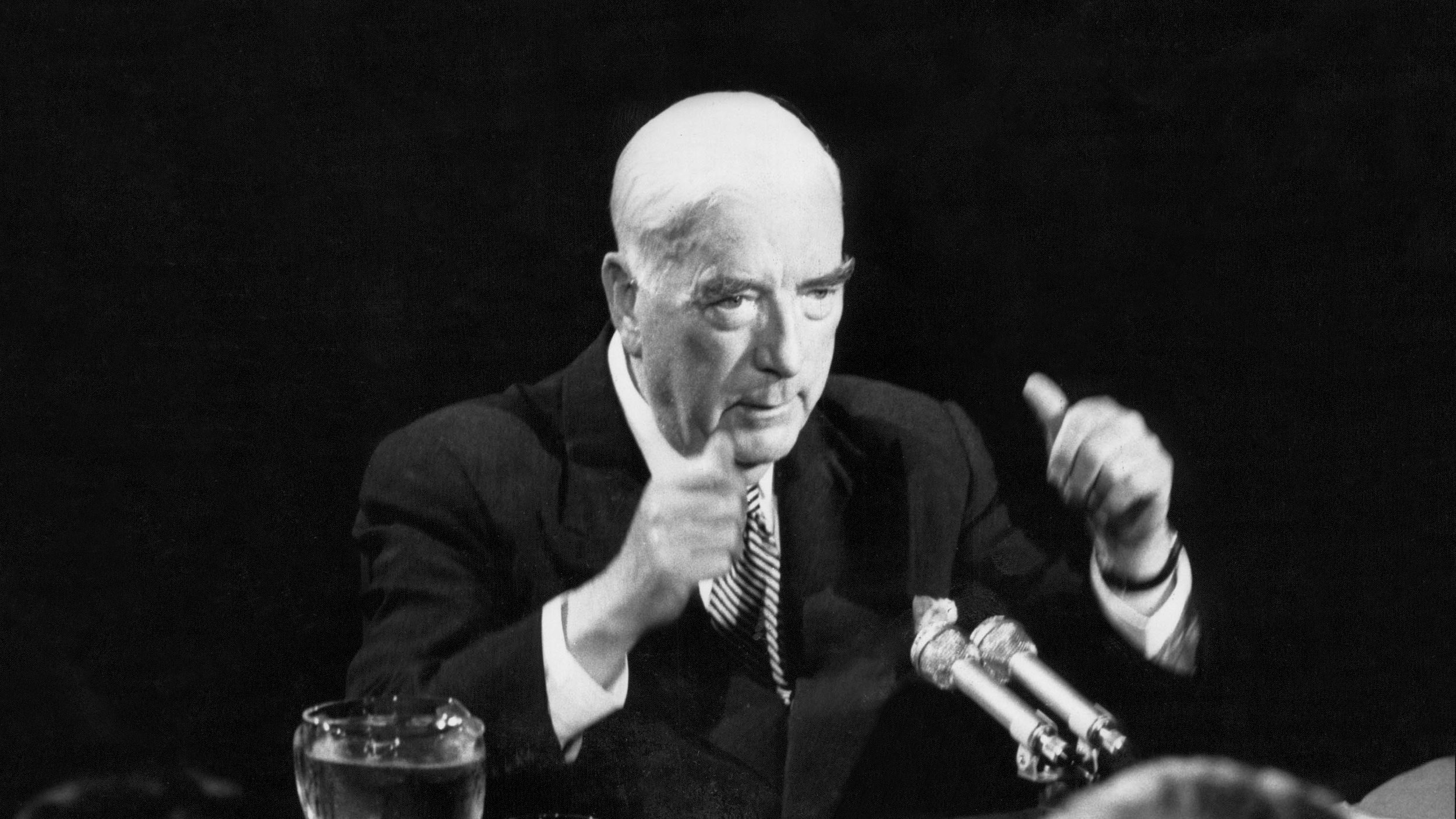

Menzies delivered his famous ‘Forgotten People’ broadcast in 1942.

Menzies spoke of a middle-class society where the person used their individual uniqueness to build a life through frugality, a home, and education to create real freedom. Freedom found as a person in a society. Key policy objectives flow from these principles.

Larry Siedentop in “Investing the Individual – The origins of Western Liberalism”, writes:

‘Yet Liberalism rests on the moral assumptions provided by Christianity. It preserves Christian ontology without the metaphysics of salvation.’

There is no doubt that Menzies in his thinking and writing took the basis of his thoughts from the tenets of Christianity. The distinction between person and individual is one. The extension of this distinction to the feature of a society based on relationship characteristics, and not the selfishness of individualism is another. The significance of personal choice for ‘homes material, homes human, and homes spiritual’ in contrast to ‘intellectual refuge in the emotions of a crowd or ‘crowd think’ or ‘camp followers’ is another. Orthodox Christianity holds that each is equal to the other, but each has the individual capacity to further oneself at one’s own pace whilst still being a member of the whole. Conformity, complacency, or elitism do not sit in this message of Menzies. What there is, is self-fulfilment within a society to satisfy personal security, both material, and spiritual.

‘Homes material’, ‘homes human’, and ‘homes spiritual’ and ongoing policy

The late Sir John Carrick, a man with an extraordinary mind and insight, who was always happy to remain in the shadow of Sir Robert Menzies, observed that key policies for Australia were energy, housing, education, indigenous affairs and the arts. It might be a matter of curiosity as to why the economy is not in these key five policies. ‘Homes material’ is found in the first two, and the foundation for a prosperous Australian economy is found in the third. To pause and reflect on this is important as Australia now has the highest energy cost in the world. Australia always has been and still is an exporter of raw materials and distance is an issue. Distance means high transportation costs. Australian wages have historically been high. Energy costs need to be kept low to balance out the cost of doing business. All governments until recently looked to cheap energy. In his role as Energy Minister, Carrick’s major concern had been securing lower energy costs after the Whitlam Administration saw exploration fall, and oil shocks costs had created inflationary pressures, pressures for wage increases and higher interests, resulting in the closure of businesses.

The policy area of indigenous affairs was on the list as Australia could not have a part of its people not prospering. The arts was on the list because it was an expression of the creativity of the Australian people, an expression of our national identity.

It is an interesting observation that John Howard’s prime ministership followed to some extent these basic key policy objectives. It is also of no surprise that John Howard was well known for his ‘four corner’ analysis when considering new policy. A policy proposal had to be good for Australia, be financially responsible, be good for families and meet the four corners of Liberal Party policy objectives.

Party formation and operation

In 1944 Menzies first expressed the concept of community democratic representation in two broad based community meetings in Albury and Canberra that soon found expression within the structure of the new Liberal Party organisation. The Liberal Party through its branch structure was the primary party connection with the community. In 2023 this connection has all but gone. People do not join; people do not attend meetings, and the day-to-day brand of the Liberal Party is no longer that of a participatory organisation. As an example, the NSW organisation operated from 1944 to 1972 as a participatory organisation even when allowing for the usual ebb and flow of organisational enthusiasm.

Menzies drafted the constitution which all State Divisions of the Liberal Party took up as a founding document. This document, elegant in its drafting and simplicity, was one based on representational democracy. The governing body was the State Council, not State Executive, as is now the case in NSW. Members of the State Council had only delegates from State Divisional Conferences. Delegates from Federal Divisional Conferences had a Federal organisational structure. The State MPs were not on State Council unlike today. It was a member’s body. Parliamentarians had control of final party policy along with their parliamentary duties but not control of the membership. Menzies always said parliamentarians had enough to do as a parliamentarian if they were doing their job!

Formation of the Liberal Party meeting in 1944

Sir John Carrick was NSW State Director from 1949 to 1973. He ensured State council papers were forwarded to delegates in time for a branch meeting to occur, to permit discussion.

Branch delegates were expected to represent branch decisions at State Council meetings.

State Executive had its decisions between State Council meetings ratified at the next State Council meeting. It was a body that was manageable. Whilst Menzies had held that parliamentarians made policy because of his experience with the United Australia Party, Sir John drafted the winning 1965 NSW State election manifesto from motions from the NSW members’ Convention. This first Liberal Coalition in NSW lost in May 1976 to Neville Wran with Nick Greiner winning in 1988.

Sir John Carrick had a creedal statement which he used within the NSW Liberal Party whilst he was General Secretary:

‘Each of us has a different role to play in the Party, from the Prime Minister to the Branch Secretary, the Party Member to the Branch President and to the Local Liberal Member of Parliament. Each role is as important as the other no matter what it comprises.’

This statement has several themes. It celebrates and emphasises the equality of persons within the Liberal Party; it emphasises the importance of the Liberal Party as the central cause; and it distinguishes individual roles within the Liberal Party within the framework of organisation and equality of contribution despite the position or role.

In NSW, the emphasis on representative membership control started to change in the late 1970s when NSW State Council grew to an unmanageable size. In the 1990s State Executive took the ascendency following the Staley constitutional review. A presidential campaign flyer in 1999 carrying the words “members matter the most” was enough to have the presidential and executive election of that year put on hold for months!

It is common to hear the phrase within the NSW Liberal Party today: ‘you cannot fatten the pig on market day’, but few know that it was a Carrickism, indeed, some do not know who Sir John Carrick was. This expression meant constant campaign activity and readiness. The campaign never ceases. Carrick also said, ‘mark the difference’. He did this in several ways. He issued regular information leaflets explaining to the membership the economics of a policy position or what the policy challenges were, so they knew, and understood the decisions made by the Parliamentary Party.

Sir John created the General Secretary’s policy committees which non-party members sat on. They had expertise to generate policy ideas which fed into information leaflets or suggestions to the Parliamentary Party. Communications within the party structure were important. It encouraged extraordinarily well-informed policy debates as late as the 1980s. Factionalism was in play, but it was tempered by the administration of Sir John Carrick. He was a firm supporter of high standards of organisational ethics that included transparency as one of the measures to mark the difference. One legend has it that Graham Richardson whilst at the NSW ALP office came to inspect the Liberal Party books on Carrick’s invitation.

Sir John Carrick invented the phrase ‘You cannot fatten the pig on market day’.

A work that sits somewhat unexplored is what effect did Sir John have in his long-time role as secretary at Ash St in maintaining Liberal Party principles and these high standards of integrity. It is a work that might now never be addressed because of the passage of time, and much is oral history. Sir John took the view that a State Director was a servant of the party, and this was not a public role. However, it must be noted that Sir John’s secretary for many years was his wife. It was observed that one had to get past Lady Carrick to get into the simple office of broken floor tiles and very simple furnishings. (All this changed when Sir John left the position, and the flash corporate style descended on the ever-changing and ever moving Party headquarters in the 1970s, 80s and 90s). Lady Angela Carrick was an extraordinary person. It is quite plausible that Lady Carrick corrected versions of “We Believe’. It is entirely plausible that she voiced an opinion occasionally. Whilst this too is a thesis to be developed at another time, the point is that the Liberal Party of NSW administration was not a man’s world, far from it.

The ongoing challenge that Menzies identified

Menzies understood the forces that would strive to pull down his political philosophy. Menzies defined who were the ‘forgotten people – the middle-class of Australia’ by exclusion. He excluded:

‘[the] rich and powerful: those who control great funds and enterprises and are as a rule able to protect themselves – though it must be said that in a political sense they have as a rule showed neither comprehension nor competence. But I exclude them because, in most material difficulties, the rich can look after themselves.’

Today some might say these people are the chattering class, not affected by what they inflict on others in their objective to make more money. Others might identify them as ‘international rent seekers’; those who utilise government subsidies to increase their wealth without regard to the wider implications of their actions. A new type of economic feudalism without borders in which these people willingly participate.

Menzies defined the ‘forgotten people’ as the middle-class of Australia, excluding the ‘rich and powerful’ on one end and ‘the mass of unskilled people, almost invariably well-organised, and with their wages and conditions safeguarded by popular law’ at the other end of the scale.

Menzies excluded at the other end of the scale ‘the mass of unskilled people, almost invariably well-organised, and with their wages and conditions safeguarded by popular law’. This group of people are still here with us, and politically highly effective even if numerically less today despite efforts to increase union membership and to set wages at an enterprise level. They do have an unmitigated and significant influence on Australia’s largest pool of savings – superannuation funds. Menzies did not treat this group like the rich and powerful, rather he identified their capacity for social progress. He saw the prime object of a modern political party ‘is to give a proper measure of security and provide the conditions that will enable them to acquire skill and knowledge and individuality.’ Those who were later identified as ‘Howard’s battlers’ or the ‘aspiring classes’ might be the late 20th century equivalents of Menzies’ early 20th century identities. One cannot achieve social progress without being a person in a society, but that progress happens through the uniqueness of the individual within the person. This relationship or association between people creates the circumstances and conditions for this. The concepts go past language and move towards Menzies’ phrase ‘homes spiritual’. This the most difficult of Menzies’ phrases beckons to the spiritual satisfaction with the achievement and attainment of homes material and homes human. Menzies refers to freedom that rests in these two ‘homes’; but freedom is also found in the home of spirituality with a sense of well-being and achievement as a person.

Menzies delivered his broadcast in 1942. At the time, the European fascist states were constructing a union of state control, big business (the wealthy) and the unions to the ultimate detriment of the middle-class. Federal Opposition Leader Peter Dutton now calls the forgotten people: ‘the working poor’. This is what happened in Europe to the middle-class and the workers and more when the great experiment of fascism failed.

Socialism was another threat against capitalism and freedom of choice since the late 19th Century. Antonio Gramsci, one of the influential Marxist thinkers of the 20th century, wrote:

‘Socialism is precisely the religion that must overwhelm Christianity … In the new order, socialism will triumph by first capturing the culture via infiltration of schools, universities, churches & the media by transforming the consciousness of society.’

The antithesis to ‘homes material’, ‘homes human’ and ‘homes spiritual’ is socialism. The battles lines were drawn on this when Menzies sat down in 1942 at the 2UE radio microphone in Sydney to broadcast the ‘Forgotten People’. Menzies understood these forces. He knew both inherently and from observations of his time of the destructiveness to free choice when society’s principles are based on socialism, fascism, and/or a dictatorship. A destruction that was deconstructing for Menzies’ ‘Forgotten People’. The movement of Deconstructionism, the ongoing vanguard of the new order, had already commenced with its first two impetuses found in the destruction and disillusionment of the great War followed by the further devastation of the Great Depression.

People do not recognise Deconstructionism for what it is. They get annoyed by individual issues and what are perceived to be controlling influences or being perceived as a victim, whilst searching for freedom as an individual. But they do not join the dots to see that each issue is part of a comprehensive strategy to pull apart our belief system and institutions piece by piece. Understanding of this beholds clarification which beholds choice which beholds action to live and protect ‘homes material’, ‘homes human’ and ‘homes spiritual’. Understanding it brings about continuous vigilance. Menzies understood this and this understanding lies at the core of his liberalism. In the ‘Forgotten People’ speech, he inferred freedom of intellect and not being ‘mustered by the emotions of the crowd’. Carrick understood this through his ‘marking the difference’. The Liberal Party then in so many ways gave an opportunity for the individual’s intellect to be exercised in making choice between Liberalism or its enemies. Both Menzies and Carrick acknowledged and understood that the Left’s propaganda and subterfuge material promising greater benefits for society at the expense of core liberal values could not go unchallenged. It also provides further understanding to Carrick’s pig and market day saying.

In the 1970s, Lord Halisham of St Marylebone, twice former Lord Chancellor, wrote of ‘limited government’ in contrast to the ever-expanding size and role of the bureaucracy and ever pervasive government as the solution to all issues. Decades earlier, Antonio Gramsci propagated a dictum that unlimited government was an effective means ‘of capturing the culture and infiltrating administrative structures to transform the consciousness of society’. The point here is that when Gramsci and Lord Halisham wrote their words the Deconstructionist movement was overt. Today it is embedded and not acknowledged. In 2023, the essence of what both men wrote needs to be loudly proclaimed. The extraordinary matter for contemplation is that Menzies had an inherent understanding and was very prescient of the two alternatives. The term ‘homes spiritual’ refers to a personal freedom attendant with choice, a free intellect to fulfill individual wishes and capacity to be a person with growth. To borrow C.S. Lewis’s phrase, ‘differentiation of vocation’; to set one’s destiny as a participant in a free society which shares this possibility and affords each person with the same capacity for choice and fulfillment. Putting the three elements together, ‘homes material’, ‘homes human’, ‘homes spiritual’, a fulfilment is achieved in body, mind, and soul through choice, and positive action. It is a recipe for a productive and fulfilled society.

Marking the difference

Some 20 years after Menzies’ Radio Broadcast, Federal President Sir William Anderson wrote words that are still relevant in 2023:

‘Liberalism should not be construed as an inflexible political doctrine, precise in its declaration of dogma. For rigidity is distasteful to the Liberal with his basic belief in independence. So, he turns from any narrow concept to find in the “liberal way of life” the common ground on which the infinite variety of individual Liberals may meet in fundamental agreement. This liberal way of life embraces spiritual, mental, and material values. It goes beyond political considerations, although only on the common ground of political platforms and action can the objectives of a truly political party be defined.’

Sir William continued and noted that freedom of the individual is the first essential of the liberal way of life. People are born with a free choice between good and evil. This freedom of choice must be theirs throughout life if they are to achieve the full stature of their development as a human being. The person must possess this freedom to err or for that person not to be right, to fail or to succeed. Sir William then ‘marked the difference’ by writing:

‘By contrast, the Socialist would attempt to eliminate the chance of failure by removing the opportunity to succeed. The Socialist’s advocacy of equality contemplates not only an equal start in the race but an equal finish.’ That is a contradiction of freedom, a denial of real opportunity.’

Then, this:

‘One current conception of freedom – freedom from something undesirable, freedom from fear, freedom from want – is a pale shadow of the liberal conception of freedom, which is freedom to do something, to be something. It is the protective approach of a State-minded generation in sharp contrast to the liberal belief in the self-directing power of personality and the liberation of living spiritual energy.’

Sir William makes two points worthy of reiteration. ‘Man’ is not merely an individual. Individuals are members of society. Society is natural. This brings the statement of liberalism to the person and the individual. The needs of nature draw people into a society. People are by nature interdependent by the needs of nature. Then there is a tension in democracy between freedom and obligation within the rule of law and order. The authoritarian states have no such tension, the state is all-important, and the individual conforms to its will. Discipline is implicit in the authoritarian state. The democratic state depends for its existence on the self-discipline of its members. He writes:

‘The story of democracy is the struggle to wrest freedom from authority and still retain authority. Under democracy the individual voluntarily surrenders the fullness of his freedom. They do so by electing representatives who will govern. Democracy is a system of liberties secured by Parliamentary Constitution. It means not so much the direct rule of the people, but the rule of law made by the representatives of the people; it may be contrasted with the rule of force, or of wealth, or even mass emotion.’

When comparing the words of Sir Willian Anderson of 1951 and Sir Robert Menzies in 1942 to current events the difference is marked! Today where the feeling or the ‘vibe’ seems to rule, where the Government is supporting ‘same job, same pay’ as a productivity measure but is really socialist equality, and with two Budgets that the serious business commentators say will fuel inflationary pressure that will hit Menzies’ ‘Forgotten People’ hardest, the comparison of a bright political philosophy to government by interest groups today is notable.

The Liberal Party of 2023 has the opportunity through these precedents to show that it is a mature broad church which understands its philosophical heritage, identifies its opponent’s emotional intellectualism, and articulates that through a party-political platform. Federally this has been down three times successfully. Whilst Australia has changed and is changing, a person with their individualism is still the foundation of our society even if socialist Deconstruction is abroad. Free choice is fundamental to ‘homes spiritual’.

Stuart Coppock is a lawyer. He was the first Liberal candidate for the Federal seat of Lindsay and was a local councillor for 21 years.